48 years after Steve Biko died in police custody, South Africa to reopen probe into anti-Apartheid icon’s death

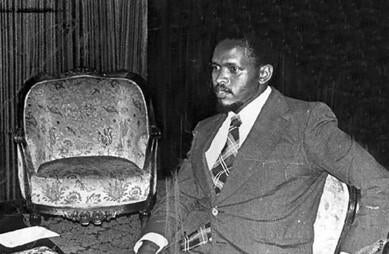

Johannesburg — South African activist and anti-apartheid leader Steve Biko died almost five decades ago at the age of 30 in police custody. Family members and others who saw his body that day said he was tortured and killed by South African police, and that he had not died from the effects of a hunger strike, as officers claimed at the time.

Prosecutors announced on Friday that they would be reopening a formal inquest into Biko’s death, exactly 48 years to the day after he died.

Biko, a liberation leader who founded and led South Africa’s Black Consciousness Movement, became one of the most globally recognized victims of the apartheid era following his 1977 death in a prison cell.

The country’s National Prosecuting Authority, in a landmark decision, confirmed it would reopen an inquest to allow judges to rule on whether an offense had been committed.

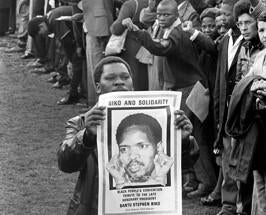

SOWETAN/THE SOWETAN/AFP/Getty

Nobody has ever been held to account for Biko’s death, and several police officers requested, but did not receive, amnesty for their alleged involvement during the hearings of South Africa’s post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

Biko was arrested at a roadblock in what was then called Grahamstown, now Makhanda, in August 1977. He was accused of violating a so-called “banning order,” a measure in the apartheid-era’s racial segregation laws that allowed authorities to restrict the movement of individuals deemed a threat.

Twenty days after his arrest he was driven over 600 miles, naked, with his legs in shackles in the back of a police vehicle, to Pretoria. He died in prison the day after arriving.

According to reports from family members and others who saw his body soon after he died, Biko was brutally tortured by apartheid regime police during his incarceration and eventually died of a brain hemorrhage.

The only government inquest into Biko’s death was carried out in 1977, decades before the end of apartheid rule, and a judge came to the conclusion that no one was to blame.

But his death was met by an international outcry, and calls for sanctions against the apartheid government and its leaders helped fuel the global movement against the racist regime.

Biko’s life was immortalized in music by Peter Gabriel’s “Biko,” just three years after his death, and then again by reggae dancehall artist Beenie Man’s “Steve Biko” in 1997. Denzel Washington played the anti-apartheid icon in the 1987 Hollywood movie “Cry Freedom.”

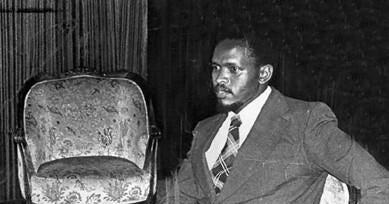

STF/AFP via Getty

Five former police officers from the South African regime’s feared Special Branch testified at the TRC that Biko had attacked one of their colleagues with a chair, and that during an ensuing scuffle to restrain him, he hit his head against the wall, causing his death.

They admitted under cross-examination, however, that they had colluded and submitted false affidavits during the initial 1977 investigation.

“My dad was a very healthy man, and we know he died of a severe brain hemorrhage,” Biko’s son Nkosinathi Biko said in an interview this week with the broadcaster Newzroom Africa. “During the TRC process it was clear under intense cross-examination that one of the men admitted that they grabbed his head and rammed it into the wall which caused his death. They were denied amnesty at the TRC because of course they lied.”

The TRC, which conducted its work between 1996 and 2001, recommended more than 300 cases for prosecution by the National Prosecuting Authority. To date, no one has been prosecuted for those alleged apartheid-era offenses, however, leaving many families, including Biko’s, frustrated.

“It’s very clear that the history books of this country need to be corrected,” Nkosinathi Biko said in the interview. “The body of my father is a living testament to his last minutes and the torture and violence that was visited upon him. We should by now have dealt with these matters 30 years into our democracy, and it should have been handled better.”

Frédéric Soltan/Corbis via Getty

In April, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa ordered an inquiry into whether previous governments had intentionally blocked investigations and prosecutions of apartheid-era crimes.

The National Prosecuting Authority has been under pressure to bring formal charges for apartheid-era crimes allegedly committed by individuals who did not receive amnesty through the TRC process, as well as to bring accountability and answers to unresolved cases of gross human rights violations during the apartheid regime.

Nkosinathi Biko said his father’s legacy was about giving and investing in a shared society, and he said setting the record straight was a vital step forward for the nation.

“I think that our sense of triumph, our sense of healing, rests in the prosecution, which is necessary in the inquests,” he said. “But it also rests in ensuring that we correct the history of this country and we accentuate the value of human life and human dignity.”