Mary Roach’s New Book ‘Replaceable You’ Addresses the Challenges of Body Part Replacement

Mary Roach’s New Book Replaceable You Explores Challenges in Replacing Body Parts

Rachel Feltman: For Scientific American’s Science Quickly, I’m Rachel Feltman.

Humans have been trying to replace ailing parts of our bodies for thousands of years, turning to prosthetic limbs, regrown noses, you name it. But creating something that works as well as our original equipment remains an enormous challenge.

Here to walk us through the struggle to replace human heads, shoulders, knees and toes is science writer Mary Roach, author of the new book Replaceable You: Adventures in Human Anatomy.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Thanks so much for coming on to chat today.

Mary Roach: Oh, thank you, Rachel, for having me on.

Feltman: So your books have explored everything from the human gut to the hunt for ghosts, scientifically speaking. What is your latest about?

Roach: Replaceable You is a look at efforts to swap out, build, replace bits and pieces of the human body. Some of the book is historical and much of it is set in the present, so it’s just about the amazing challenges, and also the progress, but the—just how complicated it is to try to create something that functions as well as what we start out with.

Feltman: And what got you interested in that topic?

Roach: I got an email from a woman who said, “I think your next book should be about pro football referees,” and I’m like, “That’s a really odd choice for me, and I don’t watch football.” But we started corresponding a bit, and she mentioned that she’s an amputee, specifically an elective amputee, meaning she had an underperforming foot, and she had multiple surgeries and still wasn’t able to really walk on it in a way that she felt she wanted to be able to do, and she used to see people walking around with prosthetics, running, hiking, and she’s like, “I want that. Why won’t somebody cut off my foot [laughs]? Somebody please cut off my foot.”

That got me thinking about replacement parts, and so that was the spark. Then I meandered down the road through another few possible chapters I might cover, and I thought, “Okay, this is the human body—that’s kind of my turf.” I like to explore our bodies, the strange and wonderful, complicated machines that they are.

Feltman: I would say that’s a pretty good inspiration story [laughs]. But …

Roach: Odd, though. She’s still after me to write a book about [laughs]—she’s like, “Okay, now you can start on that book about professional football referees [laughs].”

Feltman: [Laughs.] Maybe later.

Roach: Yeah, maybe next time, heh.

Feltman: What did you learn about this field? How has it changed in recent years, and what kinds of things are possible right now?

Roach: Oh, gosh. Well, that’s a 200-page question [laughs]. I guess I would say that the whole field is both moving very quickly and, at the same time, amazingly slow. You know you look at something like a hip replacement: the first one was done in 1938, and there’s been this progression of changes and advancements and improvements, and it’s become something effective and safe and commonly done, but it was a long road.

And, you know, and you look at stuff that’s going on now in regenerative medicine and CRISPR, what was that—like 2012? I mean, already we’re seeing treatments coming out of that. And so things are happening at a breakneck speed, but still, you know, it’s—you have the discovery. You work things out. You go to clinical trials. That’s 10 years, probably before something is ready to be released, and then you have to convince the insurance companies. Anyway, so it’s a strange mix of things happening at a really amazing pace, but also, it’s just a long haul, always.

Feltman: And could you give our listeners some examples of the kinds of parts we’re talking about replacing? Just a couple of your favorites, since, like you said, that is a 200-page question [laughs].

Roach: [Laughs.] Yeah, yeah. I started out with, with noses ’cause I—you know, the nose was the first thing that was widely replaced, partly because nasal mutilation was a, going back hundreds of years, a punishment. So it was both a punishment and a deterrent to hack someone’s nose off because everybody can see it. So there was this need for rebuilding noses. Even going back to 1,000 B.C. there were people who had the idea that you could take a little piece of the forehead or the cheek and you could cut it out, kind of flop it over onto the nose, leave it attached and rebuild a nose that way, which is astounding.

So that was, that was where it began, and now we’re talking about trying to grow things from scratch. I thought, “Because I don’t have a background in this, let’s start with something simple.” And there was a company, Stemson Therapeutics, that was attempting to grow follicles using induced pluripotent stem cells. And it was both like, “Wow, look what they’re doing,” and also, “That’s all you got?” [Laughs.]

So they would take, like, off-the-shelf induced pluripotent stem cells; they’d figured out a way to teach them to become the two kind of building blocks of a follicle. And they had these two types of cells, dermal papillae cells and keratinocytes, and the cells would kind of come together and create a primitive follicle—like, more than a blob, less than a follicle. It was producing hair, right? It was producing hairlike—hair material, but it was underneath the skin; it wasn’t coming up.

So they’re like—they called it “disorganized hair.” And they’re looking—they’re like, “We’ve gotta get it to come out of the skin. It’s gotta—” Wherever they put it, it would heal over, like skin does, and then they’re like, “We need a little tube.” And so they got these amazing engineers to create little, tiny tubes for the hair material to grow up and out of the skin, but the tubes, it turned out, they were too delicate to implant, and how are they gonna get to implant a follicle? It requires a little force to get it in there. And so that wasn’t gonna work.

And then they were threading the two types of cells on a piece of kind of thread and letting them come together, and then at some point they’d pull the thread out. And it was incredibly complicated, and it was working and exciting—and then they didn’t get enough funding, and they went out of business [laughs]. So that’s kind of the story.

Nobody’s growing organs from stem cells, whole organs; that’s still science fiction. But creating just, like, little clusters and patches and—of cells that are, maybe, you have folks looking at treatments for diabetes and, potentially, for Parkinson’s where you could, you could, in a bespoke way, take somebody’s cells, regress them to pluripotency and then turn them into the kind of neuronal cells that produce dopamine or turn them into islet cells that produce insulin. So you have this “primitive,” in quotes, but pretty exciting stuff.

Feltman: Yeah. What excites you the most about the future of some of the research you covered in the book?

Roach: I’m gonna—I mean, I don’t get into how AI is used in all of these things, but my sense is that’s gonna really speed up this work. That’s gonna make it quicker to find molecules that work, quicker—just everything may be speeded up. And, and that makes me sad that—the kind of cuts that are going on to basic research, that’s been really sad. The book was about to go to production when [the U.S. DOGE Service] kicked in, so, you know, I had to call all the labs and kind of say, “Are you still okay? What’s going on?”

But that’s not what you—you asked me what’s exciting, not what’s depressing [laughs]. Oh, it’s all, “We’re just in this period of massive potential.” And then you dive in, and you look at the challenges—it’s just very, very difficult to do something as well as the body does it. But things are moving fast.

Feltman: Your books always take you to such interesting locations. Were there any labs or other places in particular that really stuck out to you?

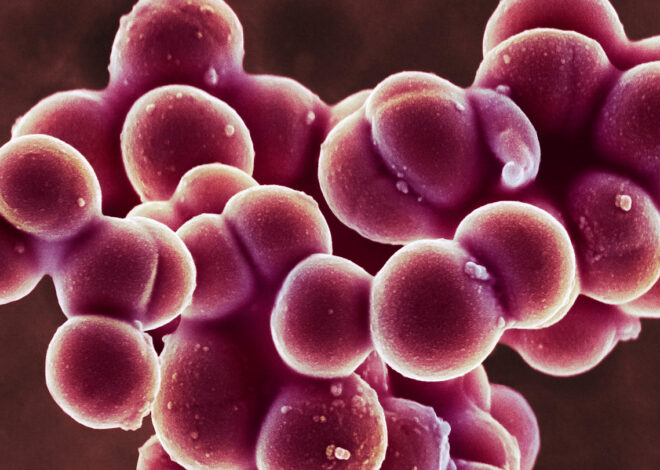

Roach: I spent time in a designated pathogen-free pigsty in China where pigs are being raised for xenotransplantation of organs. Just the idea of a highly clean [laughs]—“superclean” is the technical term—a superclean pigsty was kind of appealing, so I visited. I wasn’t allowed in. I went all the way to China, and I’m like, “Oh, over the hill there, that’s where they, that’s where they are. So how are we getting there? We’re gonna—” and they’re like, “Oh, we’re not going in.” They’re like, “You’re a massive pile of bact—

Feltman: “You’re too dirty” [laughs].

Roach: “You’re a filthy human. You don’t come anywhere near our pigs.”

That was fascinating. I got to see them in the control center; they have videos on all of the pigs. And so I got to, I got to see them but not say hello in person. But it’s kind of an amazing—I mean, they had a bunkhouse where the workers stay for three months; they’re quarantined. And then they stay there—they can’t leave. It’s just them and the pigs. The pigs are tested for 40 different bacteria and viruses and fungi. Everything is disinfected every three days. The food gets irradiated. I mean, it’s an amazing operation. And then you look on the screen, and, like, there’s a pig taking a crap, and I’m like, “Okay, it’s just a pigsty.” It’s a—I mean, you can’t train a pig to use a toilet, so.

Feltman: [Laughs.]

Roach: [Laughs.] Presumably that pig s— was really sterile and clean.

Feltman: That’s great. Thank you so much for coming on to talk about the book. Would you remind folks what it’s called?

Roach: Sure, it’s called Replaceable You, and the subtitle is Adventures in Human Anatomy.

Feltman: That’s all for today’s episode. We’ll be back on Friday to learn how one experimental musician may have composed new tunes from beyond the grave.

Science Quickly is produced by me, Rachel Feltman, along with Fonda Mwangi and Jeff DelViscio. Shayna Posses and Aaron Shattuck fact-check our show. Our theme music was composed by Dominic Smith. Subscribe to Scientific American for more up-to-date and in-depth science news.

For Scientific American, this is Rachel Feltman. See you next time!

Source:

www.scientificamerican.com

Published on 2025-09-24 10:00:00 by | Category: | Tags: