Potential Pandemic Threat: Bird and Human Flu Viruses May Combine in Cow Udders

Bird Flu and Human Flu Viruses Could Mix in Cow Udders and Spark a Pandemic

September 25, 2025

4 min read

Cow Udders Could Brew Up Dangerous New Bird Flu Strains

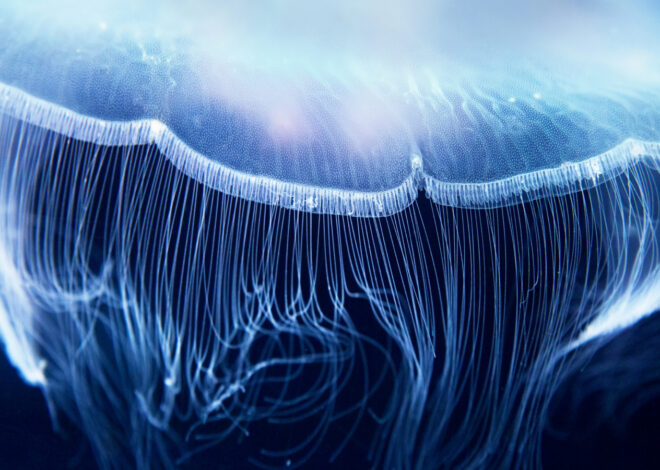

Cells in cow udders could act as a site for human flu and bird flu viruses to swap genes and generate dangerous novel strains

Cow udders may provide a hotspot for bird flu and human flu viruses to mingle.

The prospect of an outbreak of avian influenza among dairy cattle triggering a pandemic in humans is one step closer than scientists thought. New research shows that cow udder cells can be infected with human flu and bird flu viruses at the same time, which means the viruses could exchange genes and generate novel strains that would be better adapted to infecting people. The risk of this happening is low, but if it does, the consequences could be severe, experts say.

H5N1 avian influenza is widespread in wild birds, and there have been many outbreaks in poultry since 2020. In the U.S., a highly infectious form of the virus has also spread through dairy cattle herds, and 70 cases in people have been detected since February 2024. One of those human cases was fatal.

Virologists have been concerned about bird flu for decades because it has such a high mortality rate in humans. Globally, between 2003 and May 2025, there have been 976 reported cases in humans, almost half of which were fatal.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Fortunately, H5N1 hasn’t historically spread easily between people. But many researchers are concerned that if it keeps circulating in cattle, it might adapt to better infect mammals in general.

“It’s really important to stop the virus being able to spread from cow to cow because, as it does this, it adapts to be better at infecting cows,” says Eleanor Gaunt, a virologist at the University of Edinburgh. “If the virus is adapting to replicate in cows, it’s probably also improving its ability to replicate in humans and therefore increasing pandemic risk.”

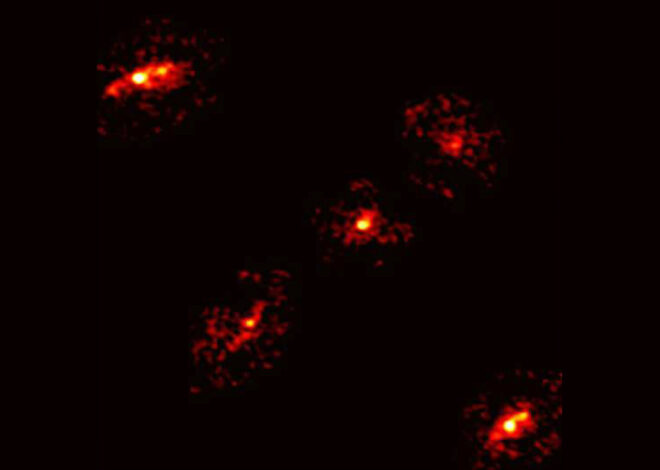

Although the recent spread of bird flu in cattle confirmed that the animals can catch that virus, it wasn’t clear whether they could catch human versions of influenza. Through tests with cells in a lab, Gaunt and her colleagues have now shown that not only can cows’ mammary glands can be infected with a human flu virus but also that many different types of influenza are able to replicate in the cow cells and that a single udder cell can be infected with human and avian flu viruses at the same time.

The researchers have concluded that cow udders are a site where viruses could swap genetic material—a process known as reassortment—and generate new flu viruses that could potentially spread more easily or cause worse illness. Their work has been posted as a preprint paper on bioRxiv and hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed.

Richard Webby, an expert in animal and human viruses at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, who was not involved in the research, agrees the findings suggest that cow udders could be infected with both forms of virus. “The concern with that is that we could get a reassortment event generating a virus that maybe has more of an ability to infect and transmit between humans,” he says.

It is hard to predict the properties of any novel virus, Webby notes. “There’s a good chance it wouldn’t be any worse than the H5 virus that’s out there. But it might just increase the replication in the human respiratory tract, giving it a little bit more opportunity for further adaptation, so it’s a concern.”

If a new virus emerges that is like nothing humans have encountered before, people won’t have immunity to it, Gaunt says.

Gaunt and her colleagues studied cells in a lab, so they haven’t seen co-infection happening in a cow on a farm. And infecting a living cow is harder, says Robert de Vries, a virologist at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, who was also not involved in the study. But he says cow udders could be a potential viral mixing pot.

Many researchers suspect human flu viruses may infect cows. No one has yet detected this, but that doesn’t mean such infections don’t happen, de Vries says. “People haven’t been testing for it because we considered this species as a nonhost,” he adds. Nevertheless, “if you set up surveillance for this, you will find it.” There is evidence that some cows have antibodies to human flu viruses, which suggests the animals have been infected by these pathogens even if the viruses themselves haven’t been detected, Gaunt says.

How U.S. cows initially caught bird flu isn’t known. Scientists suspect contact with infected wild birds seeded the initial infections, but the virus seems to have spread among cows via contaminated milking equipment, Gaunt says.

She suggests a cow could be infected with human flu if an ill farmworker wasn’t wearing personal protective equipment (if they had access to any) and if the milking equipment wasn’t disinfected between uses. Thoroughly cleaning milking equipment could help stop the spread, she says.

Just because co-infection with avian and human influenza is possible doesn’t mean it is likely, however, Webby says. Bird flu jumping into cattle in the first place is a relatively rare occurrence—as a human virus infecting the animals most likely would be, he says. “It would require a couple of rare events occurring at the same time,” he says.

But with bird flu circulating widely in U.S. herds, one of the two types of virus is already present in some cattle, which boosts the likelihood of co-infection, Gaunt says. The risk is likely to be low. Still, the more cattle that contract bird flu, the higher the chances of co-infection, so it is a risk that should be taken seriously, she says. “When we’re talking about a pandemic emergency,” Gaunt adds, “then it is generally an incredibly unlikely set of circumstances that bring it about, regardless of what virus we’re talking about.”

Source:

www.scientificamerican.com

Published on 2025-09-25 10:45:00 by | Category: | Tags: