WWI Shipwrecks in Mallows Bay Create a New Ecological Sanctuary

WWI-Era Shipwrecks in Mallows Bay Form Ecological Sanctuary

September 25, 2025

3 min read

Life Thrives on Maryland’s ‘Ghost Fleet’ of WWI-Era Shipwrecks

Nearly 100 years ago dozens of ships were abandoned in a shallow bay in the Potomac River. Today plants and animals are thriving on the skeletons of these vessels

Wrecks near the coast in Mallows Bay are becoming islands, providing novel, human-influenced habitats for a variety of terrestrial and aquatic species.

Duke Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing Lab

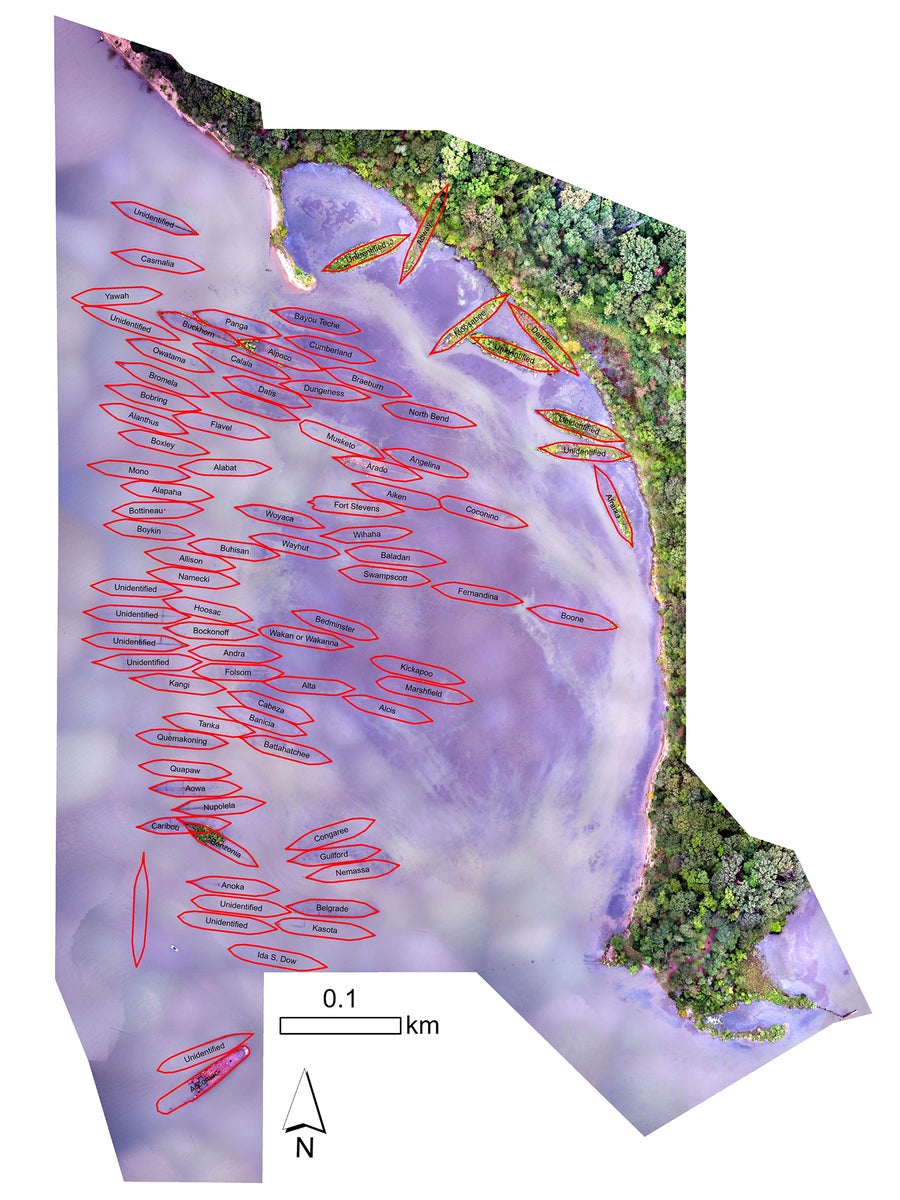

In 1929 the Western Marine & Salvage Company moved a fleet of 169 World War I–era steamships to Mallows Bay, a shallow inlet in the Potomac River, where they were burned to make any salvageable materials easier to reach. Over time, a few ships were buried under the sediment while others floated away. Today the skeletons of 147 vessels—known as the “Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay”—have turned into an ecological oasis, drone images reveal.

“I’m sure that this was, in many ways, environmentally catastrophic when it first happened,” says marine conservation biologist David Johnston, a co-author of a new study describing the area published in Scientific Data. “But life is so strong that it just takes that and makes it its own.” Johnston and his colleagues found birds, such as ospreys, nesting on wooden ruins, algae flourishing and providing nurseries for fish and trees erupting out of the sunken ships.

Grounded US Emergency Fleet vessels were burned to the waterline throughout multiple salvage periods at Mallows Bay in order to ease the recovery of their scrap metal.

United States National Archives

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Any kind of hard material attracts fauna in water, says Andrey Vedenin, a marine biologist at the Senckenberg Research Institute in Germany, who was not involved in the Mallows Bay study but co-authored a separate new paper that detailed wildlife thriving on war detritus in the Baltic Sea. That research, published in Communications Earth & Environment, found nearly five times more individual life-forms per square meter on the munition objects than on nearby sediment.

“The wildlife will, for sure, congregate in and around such structures. [They] should provide a huge variety of niches with all the complicated mazes inside the wrecks,” Vedenin says, “especially if the area is mostly unavailable for humans and human activity, like fishing.”

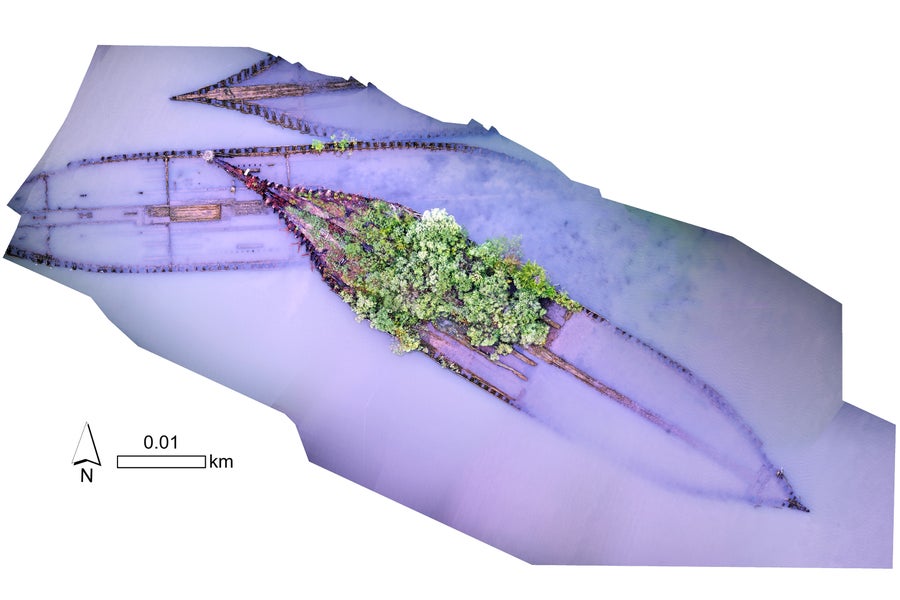

Novel, human-influenced habitats form where the wrecks of the “Ghost Fleet” meet. Here, the Alpaco and Buckhorn rest end-to-end.

Duke Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing Lab

The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, which runs into the Atlantic Ocean. When high tides arrive, water brings silt into the bay. Then, as the tide goes out, the silt settles on the ship structures. Over decades, soil accumulates, and birds or small mammals drop off seeds. “It’s like this positive spiral, right?” Johnston says. “You create a structure, animals make use of it, and in doing so, they bring seeds of other plants, which then grow.”

When Johnston and his colleagues at the Duke University Marine Lab received National Science Foundation funding to build a drone center to study coastal ecosystems, they sought a new local coast to investigate. While looking for one on Google Earth, they stumbled on a weird pattern in the Potomac. As they zoomed in, dozens of shipwrecks appeared. They had found their spot.

Duke Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing Lab

At the time, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Maryland Department of Natural Resources were developing a proposal to turn Mallows Bay into a National Marine Sanctuary. Researchers had nailed down the site’s historical and cultural importance but needed more insight into its ecological significance. Johnston’s Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing lab collected the necessary data in 2016, and Mallows Bay became a National Marine Sanctuary in 2019.

Johnston and his colleagues’ new study is based on those data, which were taken with aerial drones. One drone focused on mapping the entire fleet, another homed in on individual wrecks, and a third collected fine-detail video footage. The images were stitched together to create orthomosaics—large, high-quality maps of the ships.

Composite image, or orthomosaic, of the wreck of Benzonia in the “Ghost Fleet” of Mallows Bay, lying partially on top of the wreck of Caribou.

Duke Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing Lab

Composite image of the entire “Ghost Fleet” of Mallows Bay, with individual wrecks labelled.

Duke Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing Lab

“We are stoked that we could map the wrecks using drones and have those efforts support the designation of the marine sanctuary—we had an impact!” Johnston says. Through this project, the team has established a baseline to study how the ghost fleets react to the ongoing effects of sea-level rise and increased storminess, he adds, as well as “how each shipwreck evolves in terms of biodiversity and ecosystem function midst a rapidly changing world.”

The ecological study is one of several comparable research projects being undertaken in the sanctuary that, cumulatively, will provide useful data for everyone interested in the region, says Susan Langley, who spent 31 years as Maryland’s state underwater archaeologist before her recent retirement.

The historic shipwrecks of Mallows Bay-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary provide habitat for birds and other wildlife.

Vedenin notes that there might be even more life under the surface. “Underwater close-ups would probably reveal a huge diversity of epifauna [seafloor wildlife] living on the remnants of the ships,” he adds. “That might be an idea for future research if that has not been done yet.”

Everything in the ocean is looking for an address—a place to be, Johnston says, echoing advice he received from the late Dick Barber, a longtime ocean biogeochemist, who was on Johnston’s dissertation committee. The physical structure of shipwrecks can give marine creatures that address they’re looking for, he adds.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.

Source:

www.scientificamerican.com

Published on 2025-09-25 19:00:00 by | Category: | Tags: